Forests

Forest type

Based on their ecological

characters, the forests of Bangladesh

can be divided into tropical wet evergreen,

tropical semi-evergreen, tropical

moist deciduous, tidal, and planted

forests.

Tropical

wet evergreen forest

Evergreen plants dominate with rich

biodiversity; few semi-evergreen and

deciduous species also occur but do

not change or alter the evergreen

nature of the forests. They occur

in hilly areas of Chittagong, Chittagong

Hill Tracts (CHT), Cox's Bazar in

the SE, and Maulvi Bazar in the NE.

The top canopy trees

reach a height of 45-62 m. Due to

humidity, epiphytic orchids, ferns

and fern allies, climbers, terrestrial

ferns, mosses, aroids, and rattans

are found as undergrowth in moist

shady places. The shrubs, herbs and

grasses are fewer in number.

About 700 species

of flowering plants grow in this type

of forest. Trees like kaligarjan,

dhaligarjan, civit, dhup, kamdeb,

raktan, narkeli, tali, chundul, dhaki

jam are the common evergreen species

which constitute the uppermost canopy.

Champa, banshimul, chapalish, madar

are some of the semi-deciduous and

deciduous trees that grow sporadically.

Pitraj, chalmoogra, dephal, nageswar,

kao, jam, goda, dumur, koroi, dharmara,

tejbhal, gamar, madanmasta, assar,

moose, chatim, toon, bura, ashok,

barmala, dakrum occupy the second

storey. Sometimes Gnetum species and

Podocarpus, two gymnosperms, are met

with. Several species of bamboo are

also found in these forests.

T

T

Tropical

semi-evergreen forest

Generally evergreen in character but

deciduous plants also dominate. These

forests range in the hilly regions

of Sylhet through Chittagong, the

Chittagong Hill Tracts, Cox's Bazar,

and also in some parts of Dinajpur

district in the NW. Most of them are

subjected to jhum (slash and burn)

cultivation. Over 800 species of flowering

plants have been recorded in these

forests. They have more undergrowth

than evergreen forests. Top canopy

trees reach a height of 25-57 m. In

the valleys and moist slopes chapalish,

telsur, chundul and narkeli constitute

the top canopy; gutgutya, toon, pitraj,

nageswar, uriam, nalizam, godajam,

pitjam, dhakijam form the middle storey;

and dephal and kechuan constitute

the lower storey. On the hotter and

dryer slopes and on ridges different

species of garjan, banshimul, shimul,

shil koroi, chundul, guja batna, kamdeb,

bura gamari, bahera and moose form

the upper storey; gab, udal and shibhadi

form the middle storey and adalia,

barmala, goda, ashoka, jalpai and

darrum constitute the lower storey.

The common deciduous species are garjan,

simul, bansimul, batna, chapalish,

toon, koroi and jalpai. The flora

of these forests resembles those of

eastern Himalayas in the north and

Arakan in the south.

These forests collectively

occupy about 6,40,000 ha of land and

supply about 40% of the commercial

timber of the country. Recent introduction

of rubber plantation along with the

previous exotic teak plantation is

gradually changing the natural character

of the forests.

Tropical moist deciduous forest

Commonly known as sal forest, sal

(Shorea robusta) being the dominant

species. These forests are now distributed

in Dhaka, Mymensingh, Dinajpur and

Comilla regions. They constitute two

distinct belts (covering about 107,000

ha of land); the larger one falls

between the bhramaputra and the jamuna

rivers with a length of about 80 km

and a width of 7-20 km. This part

is known as Madhupur Garh. The other

smaller belt is situated at Sherpur

district and lies along the foothills

of the Garo Hills of India, having

a length of about 60 km and width

of 1.5-10 km. There are some smaller

remnant patches of forest areas in

Rangpur, Dinajpur, Thakurgaon, and

Naogaon districts (covering about

14,000 ha) with some remainings in

Shalvan Vihara, Mainamati and Rajeshpur

in Comilla (about 200 ha).

Until the beginning of the 20th century,

these forests existed as a continuous

belt from Comilla to Darjeeling of

India. At present, most of the forest

area is under occupation and the present

remaining stands of sal are of poor

stocking and quality, consisting of

degraded coppice and plantations.

The present notified area of this

forest is largely honeycombed with

rice fields. The forest forms more

or less a uniform canopy of 10-20

m, mostly with deciduous plants. Other

than the sal (about 90%), the other

common trees are palash, haldu, jarul

or shidah (Lagerstroemia parviflora),

bazna, hargoja, ajuli (Dillenia pentagyna),

bhela, koroi, menda (Litsea monopetala),

kushum, udhal, dephajam, bahera, kurchi,

haritaki, pitraj, sheora, sonalu,

assar, amlaki and adagash (Croton

oblongifolius). Climbers (mostly woody)

like kanchan lata, anigota, kumari

lata, gajpipal, pani lata, Dioscorea

species, satamuli, and gila occur

in these forests. A good number of

undergrowth is also recorded (about

250 species under 50 genera). The

common ones are assam lata, bhat,

boichi, moina kanta and ashal. The

significant rass is sungrass. A few

epiphytes are also recorded. Legumes,

euphrobias and convolvulous plants

also occur.

Tidal forest

The most productive forest

type in Bangladesh, they are situated

in Khulna, Patuakhali, Noakhali and

Chittagong regions along the coastal

region, and constitute about 520,000

ha. The grounds of these forests are

flooded every time at tide with seawater.

The plants have pneumatophores, with

viviparous germination, and are evergreen

in nature. Other than sundari, passur,

gewa, keora, kankra, baen, dhundul,

amoor, and dakur grow gregariously.

Turbidity and salinity of water in

the coastal zones regulate the frequency

and constituent feature of the species.

In addition to the Sundarbans,

many small islands found in the mouth

of Gangetic delta are densely covered

with tidal forests, although the sundari

tree is absent here. The pioneer plant

in the forest quickly develops on

creeks and mudbanks of streams where

deposition of silt is in progress.

Near the streams and canals, rhizophores

(having stilt roots) are common.

There are certain

forests localized to a particular

habitat conditions. These are actually

secondary formations. They include:

(i) The beach or littoral forest-

occurs along the sea beaches of Cox's

Bazar, Chittagong, Barisal and Patuakhali

regions, adjoining to tidal forests.

Jhau, kerung, ponyal, kathbadam, madar,

paras and nishinda are occasionally

associated and form different shades

of thickets. (ii) Fresh water swamp

forest- occurs in low-lying haor (large

water bodies) areas in Sylhet and

Sunamganj and also in depressions

within the hill forest area.

The area is subjected

to flooding during rainy season and

the soil is very moist. In Sylhet

area, the swamp forest is covered

with grasses like ekhra, kaghra, and

nal. Along the bank of haor areas

hijal trees often form a pure stand.

Undergrowth in these forests is mainly

cane, lantana and many large grasses

and sedges. Tree species associated

with savanna are koroi, shimul, kalhuza

(Cordia dichotoma), bhatkur (Vitex

heterophylla), and jarul. The common

undergrowth are tara (Alpinia), costus,

murta, melastoma, and nal. Other than

these specialized forests, there are

some localized forests with distinctive

floristic composition found along

the streams of hilly regions, locally

known as charas. The trees that are

commonly found along this areas are

chalet, pitaly, kanjal (Bischofia

javanica), jarul, ashoka, bhubi (Baccaurea

ramiflora), jalpai, shera and dunus.

Many epiphytes and ferns, and also

mosses are frequently found in the

composition.

In the clear felled

areas of the hill forests, the pioneer

plants that appear in the new plantation

area are fishtail palm, bura (Macaranga

species), barmala (Callicarpa arborea),

chima (Hibiscus macrophyllus), goda

(Vitex peduncularis), jiban (Trema

orientalis), nunkochi (Glochidion

species), amlaki, kurchi, elena (Antidesma),

kodom, depha jam (Cleistocalyx operculata),

koroi, udal, bazna, kanta koshoi,

toon, bhadi, gutgutya (Proteium serratum),

bata, hargaja, and various types of

grasses. Some distinct types of forests

also develop due to gradual elimination

of natural primary forests, and may

be termed as scrap jungle of the savannah

type (about 750,000 ha). These secondary

forests are often burnt to raise sungrass.

Plantation

forest

These are raised forests and are grouped

into two categories: Planted state

forest- Initial attempts to raise

plantation forests started in 1871

with teak at Kaptai in the CHT using

seeds from Myanmar. Since then plantation

forestry has become a part of the

overall clearfelling silviculture

system. Until 1920 it remained confined

to the CHT. Then it was extended to

Chittagong and Sylhet divisions. The

plantation rate per year was about

400 ha. After teak, the other common

introduced plant species are gamar,

chapalish, garjan, mahagoni, jarul,

toon, painkado and jam. In the 1950s

and 1960s wide plantation programmes

were undertaken. In 1974, the Forest

Department started planting fast growing

species like gamar, Albizia falcata,

kadam, Acacia species, Eucalyptus

species and pine on a large scale

to produce fuelwood. Planted private

forest- Traditionally homesteads grow

trees and many other crops in an effective

way. Now this forest type is developing

at a faster rate compared to the rate

of deforestation of state forests.

About 160 species are known to occur

in homestead forests. This forest

has been proved to be highly productive.

Forest distribution

The total forest area in Bangladesh

including unclassed state forest land

is about 2.25 million ha. A large

part of the area, however, has no

tree cover. Over the last three decades

forest cover declined by 2.1 percent

annually. Village groves or village

forests play a very important role

in the economy of the country. These

provide a significant portion of the

wood and firewood supply of the country.

Besides wood production, village forests

have several important uses. They

provide fruit, fodder, fuel, raw material

for small and cottage industries,

house construction materials, agricultural

implements, cart wheel, etc. The area

covered by village groves or forest

is estimated to be about 0.27 million

ha. This is not forest as per definition.

However, in the Bangladesh context

this tree cover is very significant

in many ways.

Tea garden is another category which

needs mention. A good quantity of

tree resources are available within

the tea garden. The tree cover areas

of tea gardens are fast depleting.

Approximately 2800 ha are available

under this kind of tree cover, and

distributed in Chittagong, Sylhet

and Rangamati.

A third category

of forest which is fast emerging are

the plantations on non-forest public

land, such as road side, railway embankment,

and canal banks. This marginal land

plantations in one way are substituting

for the decreasing village forests,

and are adding a new dimension to

fallow land utilization.

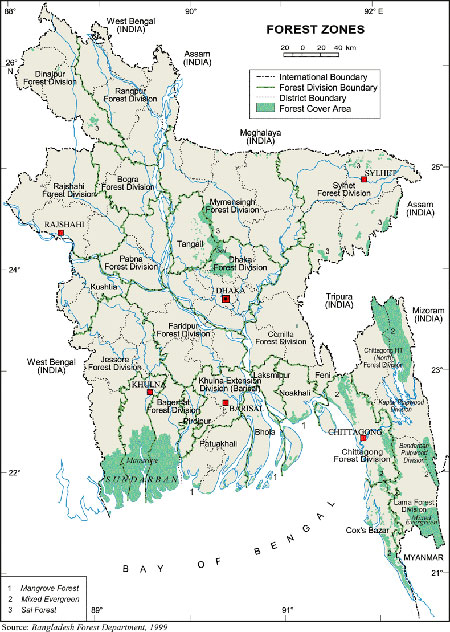

The state owned forests

(see table) of Bangladesh are distributed

in three zones: a) Hill forests in

the greater districts of Chittagong,

Chittagong Hill Tracts, and Sylhet;

b) Inland forests in the central and

northern zones; and c) Littoral forests

in the delta and coastal regions.

Status of the state-owned

forest land (in ha)

| Forest type |

Reserve forest |

Protected forest |

Vested forest |

Acquired forest |

BWDB and khas |

Unclassed state

forest |

Total |

| Hill |

594,383 |

32,303 |

2,636 |

11,004 |

-- |

721,344 |

1361,670 |

| Inland |

68,140 |

2,689 |

19,985 |

31,198 |

-- |

-- |

122,012 |

| Littoral |

656,579 |

-- |

-- |

6 |

101,526 |

-- |

758,111 |

| Total |

13,19,102 |

34,992 |

22,621 |

42,208 |

101,526 |

721,344 |

22,41,793 |

The table on state

on forests, however, does not in anyway

imply that the land is under actual

control of the Forest Department.

Much of the land is under the occupation

of encroachers. The encroachment is

quite high in the inland sal forests.

Observations since 1985 indicate that

encroachment and shifting cultivation

is on an increase in the Chittagong

Hill Tracts.

The hill forests occupy more than

half of the forests of the country.

These forests are important from economic

and environment perspectives. The

description given below mostly applies

to the forests of greater Chittagong

Hill Tracts and Chittagong. The forests

of Sylhet are extension of the forests

of Chittagong Hill Tracts and Chittagong.

The major hill reserve forests are

Kassalong (including Maini Head Water

Reserve), Rhankhiang, Sitapahar, Sangu,

Mata Muhuri, Chittagong, Cox's Bazar,

and Sylhet reserve forests. Sitapahar

was the first forest reserve in the

hills and was declared as such in

1875. About the time government appointed

professionals to manage forests. During

the first decade of the last century,

survey and demarcation of most of

the forest areas took place. Forest

department started tree plantations

at Sitapahar in 1871. Thereafter teak

plantation continued on a regular

basis. The clear felling with artificial

planting programme which was introduced

to Sitaphar extended to Kassalang

and Rankhiang reserves. In the mid-sixties

the Forest Industries Development

Corporation was established to conduct

mechanical extractions and up to 1000

ha of forests of Kassalang and Rankhiang

plantations, mainly of teak were raised.

A moderate area of 5,037 ha of plantations

were raised in the Matamuhuri reserves.

The Chittagong Hill

Tracts contains over 700 thousand

ha Unclassed State Forests (USF),

which are subject to shifting cultivation.

A part of USF spreading over Bandarban,

Khagrachari, and Lama has been taken

over by Forest Department and plantations

have been raised there. Up to 1990,

about 48,000 ha of plantations of

teak and other species have been raised.

Inventory of Chittagong and Cox's

Bazar was made in 1987. Out of 52,471

ha of natural forest area about 38%

was found to have small crown secondary

disturbed high forest; 13% good quality

large crown forests, 1% Garjan cover,

and remaining 48% brush with scattered

trees. In the inventory it was further

seen that only 17,862 ha of plantations

out of 38,852 ha of plantations was

raised ie approximately 21,000 ha

of the plantation area was lost. The

loss is attributed to encroachment,

illicit removal, and the ravages of

the World War II (1941-45) and 1971

liberation war.

In Cox's Bazar out

of 24,438 ha of natural forests, 57%

consists of small crowned secondary

disturbed forests, 42% relatively

good quality forests and the remainder

are all disturbed forests. The high

proportion of secondary forest is

a result of large scale selective

harvesting during the war periods.

It was also revealed that out of 38,000

ha of plantations raised in the division

only 24,210 ha survived (1991), ie,

approximately 30% of the plantations

are poorly stocked. Due to recent

mass migration of Rohingyas from adjacent

Myanmar and their camping in the forests

of Cox's Bazar, the condition has

further deteriorated.

Sylhet forest areas

were part of Assam prior to 1947.

Not much of early records about the

forest is available; the inventory,

however, shows that in Sylhet 13,802

ha of plantations exist.

Inland sal forest

The sal forests are presently distributed

in the districts of Dhaka, Tangail,

Mymensingh and Dinajpur. Rangpur,

Rajshahi and Comilla have little denuded

scattered areas of forests. In the

past quite a vast area of Mymensingh,

Tangail and Dhaka was occupied by

sal forests.

The inland sal forests

were under private ownership till

1950. The forest of the central zone

of Bhawal in Gazipur district, and

Atia in Tangail have, however, been

under partial management of Forest

Department under an agreement with

the owner. Until 1917, the owner managed

all the forests. The first management

plan for Bhawal forests appeared in

1917 and for Atia forests in 1934.

After partition in 1947, forest department

divided these forests into two working

circles. One was timber and conversion

working circle where clear felling

followed artificial plantation, keeping

the rotation to 70-80 years, and the

second was coppice working circle,

keeping the rotation to 25 years.

Before 1959, the

forest areas of Dinajpur, Rangpur

and Rajshahi remained under the control

of proprietors. Since there was indiscriminate

felling, the Forest Department prepared

a management plan in this year. The

plan prescribed three working circles:

conversion, coppice and afforestation.

In 1976 the plan was revised to create

two working circles: community forestry

working circle, and commercial working

circle. The plan did not work and

65% of the forest is now highly degraded

or encroached.

The littoral

mangrove forests

There are two tracts of littoral forests.

The smaller one is the chakaria Sundarbans.

It lies in the delta of the matamuhari

river in Cox's Bazar district. It

was declared as Reserved Forest in

the later part of the last century.

Though management plan for the area

existed since 1911, demand for forest

produce and fish culture led to illegal

removal and artificial inundation

of the forest. Bangladesh government

transferred about 3,233 ha of forests

to shrimp cultivation. Uncontrolled

shrimp cultivation and establishment

of seasonal salt beds cleared the

remaining forests.

Sundarbans

in the delta of the Ganges and Brahmaputra

stretches from the Hughly river to

the Rabnabad island, and extends inland,

in places, as far as 160 km. Two-thirds

of the forest area is within Bangladesh.

In the Eighteenth Century, forests

were double their present size. Uncontrolled

deforestation and settlement of land

led to reduction of forest size, and

the the Sundarbans was declared as

a Reserve Forest in 1875. In area

(about 557285 ha) though Sundarbans

remain intact, crops have deteriorated

substantially due to increase in salinity,

top dying of Sundri, and tectonic

movement. Through its own initiative,

the Forest Department has started

a coastal afforestation programme

in the early sixties to create a protective

belt in the coastal offshore and in

the islands having no tree cover.

A substantial extent of plantations

in the coastal regions have been raised

and mini-littoral forests now exist

in the coastal belts.

Present distribution

and area (ha) of different forest

types under different forest divisions

| |

Reserved

forest |

Acquired

forest |

Protected

forest |

Vested

forest |

Unclassed

state forest |

Khas |

Total |

| Hill forest |

5,94,383 |

11,004 |

32,303 |

2,636 |

7,21,344 |

-- |

13,61,670 |

| CHT(North) |

1,59,379 |

-- |

-- |

-- |

1,53,063 |

-- |

3,12,442 |

| CHT(South) |

82,161 |

-- |

-- |

-- |

1,72,721 |

-- |

2,54,882 |

| Bandarban USF |

40,198 |

-- |

-- |

-- |

78,592 |

-- |

1,18,790 |

| Pulpwood Bandarban

|

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

58,236 |

-- |

58,236 |

| Lama |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

75,149 |

-- |

75,149 |

| USF Rangamati |

12,801 |

-- |

-- |

-- |

89,694 |

-- |

1,02,495 |

| Jhum Control |

12,903 |

-- |

-- |

-- |

9,600 |

-- |

22,503 |

| Pulpwood Kaptai

|

29,279 |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

29,279 |

| Khagrachari USF |

1,409 |

-- |

-- |

-- |

82,073 |

-- |

83,482 |

| Chittagong |

82,307 |

5,096 |

19,873 |

2,636 |

-- |

-- |

1,09,912 |

| Cox's Bazar |

1,04,103 |

1,241 |

12,430 |

-- |

-- |

-- |

1,17,774 |

| Sylhet |

69,843 |

4,667 |

-- |

-- |

2,215 |

-- |

76,725 |

| Inland forest |

68,140 |

31,198 |

2,689 |

19,985 |

-- |

-- |

1,22,012 |

| Dhaka |

26,221 |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

26,221 |

| Tangail |

22,460 |

27,287 |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

49,747 |

| Mymensingh |

13,467 |

-- |

-- |

15,019 |

-- |

-- |

28,486 |

| Dinajpur |

5,037 |

387 |

-- |

4,681 |

-- |

-- |

10,105 |

| Rangpur |

763 |

1,697 |

263 |

-- |

-- |

-- |

2,723 |

| Rajshahi |

192 |

11 |

2,426 |

276 |

-- |

-- |

2,905 |

| Comilla Extn |

-- |

1,696 |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

1,696 |

| Dhaka Extn (south) |

-- |

-- |

-- |

9 |

-- |

-- |

9 |

| Kushtia Extn |

-- |

8 |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

8 |

| Bogra Extn |

-- |

7 |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

7 |

| Faridpur Extn

|

-- |

10 |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

10 |

| Jessore Extn

|

-- |

9 |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

9 |

| Botanical garden,

Dhaka |

-- |

86 |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

86 |

| Littoral forest |

6,56,579 |

6 |

-- |

-- |

-- |

101,526 |

75,811 |

| Sundarbans |

5,57,285 |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

5,77,285 |

| Bhola CA |

2,236 |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

24,304 |

26,540 |

| Patuakhali CA |

8,571 |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

13,293 |

21,864 |

| Noakhali CA |

35,741 |

6 |

-- |

-- |

-- |

54,618 |

90,365 |

| Chittagong CA |

32,746 |

-- |

-- |

-- |

-- |

9,311 |

42,057 |

| Total |

13,19,102 |

42,208 |

34,992 |

22,621 |

7,21,344 |

1,01,526 |

22,41,793 |

Abbreviations CHT-Chittagong

Hill Tracts, USF- Unclassed State

Forest, Extn-Extension, CA-Coastal

Afforestation includes Matamuhuri

Reserve.

Source: Forestry

Master Plan (Forest Management)

Forest resource

In terms of forest land, the Chittagong

Hill Tracts forest division on the

southeastern border of the country

contributes about 47%, followed by

the Sundarbans and Patuakhali coastal

divisions, about 27%. The northwestern

region, including Dinajpur, Bogra,

Rajshahi and Rangpur districts, has

less than one percent state forestland.

The western region, ie Jessore, Kushtia,

Faridpur and Barisal, has slightly

more than one percent. And yet after

the agriculture sector, forestry is

one of the major economic activities,

contributing to about 3% GDP of the

country.

At least about 1,000

species of forest plants are economically

important; of these about 400 are

considered as tree species and about

450 as medicinally important. About

50 tree species and about 100 shrubs

and herbs are viewed as commercially

important. Bangladesh Forestry sector

consists mainly of the primary production

of forest products. Except pulp, paper

and board mills, the secondary sector

is weakly developed and undercapitalized.

Logs and bamboo, the two main industrial

raw materials, come mostly from private

lands; and also from Government managed

forestlands.

Official records

show that Government forest land produces

about 5,50,000 m3 of roundwood and

about 65 million pieces of bamboo

annually. In 1997, the value of the

forestry sector has been estimated

at Taka 21 billion (US $ 537 million),

80% of which comes from primary, 11%

from secondary round wood processing,

and 3% from non-wood products. Saw-log

production is of the largest single

value, making up to 42% (Tk 9 billion),

while fuelwood production contributes

27% (Tk. 5.8 billion). Bamboo production

is at 13% (Tk 2.9 billion). Solid

wood processing, principally saw milling,

adds about 6%, and pulps and paper

production just over 4% of added value.

Tertiary wood manufacturing production,

mainly furniture and cabinet making,

is responsible for about 1%. Estimated

total present employment is about

8,00,000 persons. However, considering

the seasonal nature of work, people

benefiting directly from forestry

related works would be about 1.3 million.

Fuelwood, after solid wood, is the

next important forest resource. Of

total forest products, about 65% are

consumed as fuelwood. In 1995, total

regulated supply was 6.5 million m3

against the demand of 8.27 million

m3.

Hill forests are

treasure-houses of forest resources.

These forests are classified as subtropical

evergreen forests, semi-evergreen

forests and bamboo forests. The most

abundant but important timber trees

are garjan, teak, chapalish, gamar,

telsur, jam, jarul, civit, raktan,

champa, narkeli, teli, chundul, chikrassia

and koroi.

The next important

natural forest resources are the Sunderbans

forests. Government management of

these forests began in the 1870's

under the system of select felling

and natural regeneration. Subsequently,

in the 1930's a system of clear felling

by plantation appeared. During the

Second World War, these forests were

exploited on a large scale and the

practice continued after independence

in 1947 to meet the rising demand

of forest products. Then management

practice was raised for long (40 years)

and short (20 years) rotation cycles.

Following the establishment of Khulna

Newsprint Mills in 1959 and many other

Khulna based forest industries, the

forest management intensity increased.

Logs, timber, fuelwood and golpata

leaves are major produces of the forests,

and are mostly collected on the basis

of collection permits.

At present, Sal forests

are largely composed of two remnant

tracts. One of them is some 105,000

ha in the districts of Tangail and

Mymensingh. The second, one is the

Barind tract, covering scattered patches

of some 14,000 ha in the northwest

districts. Unlike other areas under

the control of the Forest Department,

these areas were not put under Government

management for a long period, since

they were nationalised in the 1950s.

The present notified Sal forests area

is actually honey-combed with habitations

and rice fields. These forests mainly

supply sal timber and logs along with

many other soft wood and firewood.

Bamboo is the most

important non-wood forest resource

in Bangladesh. Some 10 species occur

naturally in forest, which account

for about 20% of the national stock.

Muli (Melocanna baccifera) is the

most prominent. Forests of Chittagong

and the Chittagong Hill Tracts are

the richest sources of bamboo, followed

by the Sylhet hill forests. The rest

come from village groves distributed

throughout the country.

Non-wood forest resources

as a group, apart from their economic

value, represent the bulk of diversity

in natural forests. The situation

with regard to the management of non-wood

forest products in the natural forests

is far from satisfactory. Hundreds

of items are exploited daily from

the forests by local inhabitants.

Of the thatching and weaving resources,

sungrass is used extensively in rural

areas. The production of sungrass

is about 2 million bundles. It grows

abundantly in the denuded and Savannah

forests, mostly those in the eastern

hilly forests. Leaf of golpata (Nypa

fruticans) of the Sundarbans is an

important thatching material in the

southern districts. The annual production

is about 70,000 m tons. Rattan, an

important resource of hill forests,

is also cultivated as a homestead

plant, and is used for making furniture,

baskets, and a number of fancy articles;

the harvest rate being 1,00,000 running

metres.

Murta, a reed plant,

is used for making sleeping mats,

bags, baskets and many utility items.

It grows in both natural and homestead

forests. Nowadays, inflorescence of

a grass, named phuljharu (Thesalonaena

maxima) used to make brooms is an

economic material of hill forests.

About 500 species of plants having

medicinal properties occur in the

forests of Bangladesh. Depending on

the phytochemical contents, different

parts are collected and used in preparations

of indigenous and folk medical formulations.

There are about 500 Unani and Aurvedic

medicine preparing units in Bangladesh.

Current supply of plant materials

for indigenous medicine is about 800

m tons.

Mangrove forests

of Bangladesh are a home of estuarine

fishes, shrimps and crabs. Some 10,000

m tons of fish is collected from the

Sundarbans area annually. Honey collectors

collect honey and bee-wax from this

forest. Annual honey collection from

the Sundarbans alone is about 150

m tons.

Area under

forest by type of forest

| (Sq.miles)

|

Year

|

WAPDA

& Khash land |

Garden

area |

Reserve

forest |

Acquired

forest |

Vested

forest |

Protected

forests |

Unclassed

state forest |

Total |

%

of total area |

| 1975-76

|

47.75

|

0.33

|

4430

|

365

|

41

|

222

|

3502

|

8608

|

15.48

|

| 1976-77

|

47.75

|

0.33

|

5104

|

365

|

41

|

222

|

3502

|

9282

|

16.70

|

| 1977-78

|

48.00

|

- |

5101

|

367

|

41

|

222

|

3513

|

9292

|

16.71

|

| 1978-79

|

47.80

|

- |

5129

|

341

|

43

|

222

|

3517

|

9299

|

16.73

|

| 1979-80

|

47.80

|

- |

5427

|

346

|

42

|

222

|

3521

|

9606

|

17.28

|

| 1980-81

|

47.80

|

- |

5422

|

399

|

41

|

222

|

3440

|

9572

|

17.22

|

| 1981-82

|

48.00

|

- |

5422

|

397

|

42

|

222

|

3498

|

9629

|

17.32

|

| 1982-83

|

48.00

|

- |

5425

|

311

|

42

|

222

|

1553

|

7601

|

13.67

|

| 1983-84

|

787.29

|

- |

4893

|

306

|

41

|

222

|

1440

|

7689

|

13.83

|

| 1984-85

|

47.80

|

0.34

|

5644

|

268

|

35

|

231

|

1768

|

7994

|

14.38

|

| 1985-86

|

54.71

|

0.34

|

5718

|

262

|

35

|

207

|

2443

|

8720

|

15.68

|

| 1986-87

|

46.15

|

0.34

|

4882

|

361

|

35

|

206

|

1578

|

7108

|

13.40

|

| 1987-88

|

54.70

|

0.34

|

5097

|

447

|

35

|

206

|

6823

|

7420

|

13.45

|

| 1988-89

|

50.00

|

na

|

4353

|

492

|

97

|

193

|

1390

|

7181

|

12.50

|

| 1989-90

|

400.60

|

na

|

5063

|

156

|

87

|

143

|

1313

|

7162

|

12.60

|

| 1990-91

|

369.00

|

na

|

5028

|

157

|

87

|

202

|

1335

|

7178

|

12.81

|

| 1991-92

|

51.00

|

na

|

5092

|

496

|

54

|

197

|

1433

|

7323

|

13.08

|

| 1992-93

|

481.72

|

na

|

4689

|

603

|

31

|

145

|

1417

|

7367

|

13.16

|

| 1993-94

|

151.68

|

na

|

5109

|

515

|

32

|

193

|

1371

|

7371

|

13.16

|

| 1994-95

|

272.55

|

na

|

5643

|

372

|

33

|

149

|

1840

|

8461

|

13.60

|

| 1995-96

|

272.55

|

na

|

5643

|

372

|

33

|

149

|

1840

|

8461

|

13.60

|

| 2002-03

|

92.99

|

na

|

6996

|

33

|

15

|

143

|

2749

|

10028

|

17.50

|

| Source:

Department of Forest |

Forest product

Considering forest habitats, forest

products are of two types: (i) Land

forest products; and (ii) Littoral

forest products. These can further

be categorised as non-timber, and

timber forest products.

Among the various

uses of the forest products mention

may be made about the following:

House construction

and building materials. Both sawn

wood and round timber as well as bamboo

are used. Assuming the economic life

of the house to be 25 years, the consumption

per capita/annum is 0.0068 m3 for

building construction.

Furniture and fixtures

Numerous items are included in the

furniture and fixture categories.

The adjusted weight average is 0.0664

m3 per capita for the life of the

furniture. Per capita consumption

is 0.0026 m3/annum when the economic

life of the furniture is considered

to be 25 years.

Transport equipment

Wood is the main component for making

almost all rural transports including

bullock cart, buffalo cart, boat,

rickshaw, carriage van, hackney carriage,

palanquin (Palki), and duli. Wood

has also been used for making modern

mechanized transports like bus, truck,

launch and ship. The adjusted weight

average is 0.00721 m3 per capita.

Considering the economic life of the

transport equipment to be 20 years,

the annual per capita consumption

is 0.00036 m3.

Agricultural implements

Traditional agricultural implements

include various equipment and tools

which are made from wood. The adjusted

weight average is 0.0276 m3. Assuming

the economic life of agricultural

implements to be 20 years, per capita

consumption is 0.0014 m3/annum.

Pulp, paper and newsprint

Among forest based industries, pulp,

newsprint and paper manufacturing

occupy dominant positions. There are

three paper mills: the Karnafuli Paper

Mill (KPM), North Bengal Paper Mill

(NBPM) and Sonali Paper and Board

Mills Ltd. All these mills manufacture

industrial grade papers and paperboard.

There is only one newsprint mill located

at Khulna. Except NBPM, all paper

mills consume wood and/or bamboo pulp

for their production.

Wood-based panel

products These include a wide variety

of semi-finished and intermediate

wood-products like hard board, particle

board, plain wood text, veneer board,

plywood tea chests, flash doors, windows,

etc made by using wood (and wood by-product

such as saw dust). Both private and

public sector enterprises are engaged

in the production of panel products.

Annual average requirement of saw-log

in these units is about 97 thousand

m3.

Fuel and firewood

More than 80% of the total fuel and

firewood are procured from forests.

Of the total fuel wood, nearly 85%

is used in rural areas and 15% in

urban areas. Besides fuel wood, almost

all firewood are used for small industries

like brick fields. The estimated national

demand for fuel wood is about 7975.49

thousand m3.

Rubber products Rubber

is a monotype forest product. Bangladesh

has a good number of rubber gardens

in Chittagong, Sylhet and Madhupur

areas. The production of Rubber in

Bangladesh was 2966.58 and 3101.21

thousand kg in 1997-98 and 1998-99

respectively.

Other miscellaneous wood and forest

products Among miscellaneous wood

products, match manufacturing occupies

a prominent place. Other major items

include pencil, slate and scale production,

toy manufacturing, electrical and

telephone poles, textile and jute

mill spares and accessories, etc.

In addition, some handicraft items

are manufactured from some forest-based

small industries. Golpata (Nypa fruticans),

collected from the Sundarbans, is

used for roofing.

Non-timber forest

product Many small industries, private

and government handicrafts and cottage

industries are based on non-timber

forest materials. Many of the products

are exported to different countries.

A good number of craftsmen are employed

in these industries. Some of the most

important non-timber plants and plant-products

include bamboo (for making houses,

furniture and souvenir items), rattan

or cane (for making furniture and

luxury souvenir items), sungrass (for

house roofing/thatching), pati pata

and hogla (for floor mats), nipa palm

or golpata (for thatching and roofing),

forest honey (mainly from the Sundarbans),

Gewa (raw materials of Khulna Paper

Mill for producing newsprint), and

medicinal plants (eg Amlaki, Bohera,

Horitaki, Swarpagandha, Kurchi, Arjun,

Basok, Swatamuli, Akanda, Dumur, Ulat-chandal,

Anantamul, Tulshi, Nisindha etc).

Forest management

No scientific attempt was made anywhere

in the subcontinent to conserve the

forests before the advent of British

rule. Even in the early days of British

rule, there was much wasteful exploitation

of forests to meet the requirements

of the people. In 1862, on his way

to Delhi from Burma (Myanmar), Brandis

inspected a part of the forests of

Bengal and made a note of the state

of the forests resources of this region.

This marked the beginning of forest

management of Bangladesh. In 1864,

Anderson, Superintendent of Calcutta

Botanical Garden, was appointed as

the First Conservator of Forests of

the Lower Provinces of Bengal and

Assam (now a part of it is in Bangladesh).

Preliminary investigations and enquiries

started by him led to the reservation

of forest areas. In 1871, about 14,685

sq km of hill forests were declared

Government forests. In 1875, the first

forest reserves were declared. The

first forest reserves were in Sitapahar

(currently under Chittagong Hill Tracts

South Division) and in the Sundarbans.

The first management

plan in Bengal was prepared for the

Sundarbans (tidal forests) in 1892.

A management plan for Hill forests

was prepared at the beginning of the

20th century. The management plan

of sal forests was prepared much later.

With the partition

of India in 1947, eastern and northeastern

part of hill forests and unclassed

state forests of Bengal, some parts

of Assam, plainland sal forests, and

most of the Sundarbans forests fell

within East Pakistan. Plantation of

valuable species and extraction of

timber were the main stay of management

practices. Forest Industries Development

Corporation was set up in the early

sixties in an effort to extract timber

from the most inaccessible areas.

The target of plantations was raised

from a few hundred hectares to 4,000

hectares in the mid-sixties. A number

of economic crops like rubber, cashewnut

etc, were also introduced. In the

late sixties, coastal plantations

were also started in the new accretions

of the bay of bengal. The National

Forest Policy of Bangladesh was formulated

in 1979.

Forest management

situation

The Hill Forests are managed under

the clear felling system followed

by artificial regeneration with valuable

species with a rotation of 60 years

(long rotation) and 30 years (short

rotation). The bamboo appears either

as pure stand or as understorey.

The inland sal forests

are managed under coppice system with

a rotation of 25 years. Areas where

Sal (Shorea robusta) trees are comparatively

fewer are managed under clear felling

system followed by artificial regeneration

mostly with Sal and other suitable

species.

The tidal forests

are managed under selection system

followed by natural regeneration with

a felling cycle of 20 years. Afforestation

of coastal lands, offshore islands

and new formations has been undertaken

in the last three decades with mangrove

and other suitable species.

Forest management planning Hill forests-

(i) to convert the existing irregular

forests into regular ones replacing

non-economic trees by valuable and

fast-growing species; (ii) to prevent

denudation in the hills and erosion

of the soil and silting up of rivers;

(iii) to afforest barren areas with

a view to increasing the forest wealth;

(iv) to preserve and propagate wildlife;

and (v) to derive maximum economic

benefits under the principles of sustained

yield in practice.

Tidal forests- (i)

maintenance of the forest stand and

its gradual conversion into regular

selection forests with a balanced

distribution of age classes; (ii)

to afforest newly accreted lands in

an effort to reclaim land; and (iii)

to maintain a sustained supply of

timber, firewood, pulpwood, thatching

materials, and other minor forest

produces for local people and existing

industries.

Inland sal forests-

(i) to bring scientific management

and gradual conversion of the irregular

forest into a series of age classes;

(ii) to supply large sized house posts

and firewood; and (iii) to create

recreational facilities. [Syed Salamat

Ali]

Forest policies

and acts

The National Forest

Policy of 1894 provides the basic

guidelines for the formulation of

acts and rules for the management

of forests in the country. The earliest

attempt to enunciate the need of conserving

forest resources was made in 1855

by the government of British India

through the promulgation of the Charter

of Indian Forests. Prior to this charter

there were only scanty regulations

regarding the felling of trees for

revenue.

The first formal

Forest Policy that was declared in

1894 included the following features:

(1) State forests are to be administered

for public benefit at large, through

regulations of rights and privileges

of the people near the forest. (2)

Forests were categorized as (a) Hill

forests/Protection forests, (b) Economically

important/Production forests, (c)

Minor forests, and (d) Pastureland.

(3) Forests situated on hill slopes

should be conserved to protect the

cultivated plains situated downstream.

(4) Valuable forests should be managed

to yield state revenue. (5) Land suitable

for cultivation within the forest

should be made available for cultivation,

provided that such conversions did

not harm forests and were permanent

in nature. (6) Local population should

be allowed to exercise grazing rights

in low yielding forests.

After the partition

of India in 1947, the policy was not

relevant for the new state of Pakistan

which inherited forest cover for less

than 2% of its territory. The existing

policy neither contemplated the increase

of forest area nor emphasized sustained

harvest from existing forests. Furthermore,

it excluded private forests from its

ambit. These deficiencies were recognized

in the Pakistan Forestry Conference

held in 1949. The conference guidelines

provided improvement upon the Policy

Statement of 1894 and a new Forest

Policy was announced in 1955.

The Forest Policy

of 1955 was further revised and the

Forest Policy of 1962 was introduced.

The Forest Policy of 1955 and 1962

laid emphasis on the exploitation

of forest produce, particularly from

East Pakistan. The policies did not

help the development of forestry in

Bangladesh and were not very favourable

for all round growth of forestry.

In addition, increase in population

and increased demand for food and

other essentials resulted in heavy

pressure on forestland, leading to

ecological degradation. Even though

Bangladesh became independent in 1971,

its National Forest Policy was not

announced until 1979.

The policy statement

of 1979 is very general and vague.

Most of the crucial aspects such as

functional classification and use

of forest land, role of forest as

the ecological foundation of sustainable

biological productivity, community

participation in forestry, etc did

not get any mention in the policy

statement. Consequently, the government

decided to amend the Forest Policy

of 1979. The amended Forest Policy,

known as Forest Policy, 1994, was

approved by the government on 31 May

1995. Following were taken into consideration

while revising the forest policy:

the clauses of public utility as mentioned

in the constitution; the role of forests

in the socio-economic development

of the country, including the environment;

adoption of national policy regarding

agriculture, industry, cottage industry

and other sectors; and the treaties,

protocols and conventions related

to environment and forests.

In the early 1990s,

a 20-year Forestry Sector Master Plan

(FSMP, 1993-2012) was developed, which

aims to bring 20% of the country's

land area under tree cover. It has

three major investment programs: (a)

forest production and management;

(b) wood-based industries; and (c)

participatory forestry. Of the two

scenarios in the FSMP, the High Development

Scenario envisages an investment of

about US $2 billion in the forestry

sector.

The latest Forest

Policy (1994) viewed equitable distribution

of benefits among the people, especially

those whose livelihood depend on trees

and forests; and people's participation

in afforestation programmes and incorporation

of people's opinions and suggestions

in the planning and decision-making

process.

The people-centred

objectives of the policy are: creation

of rural employment opportunities

and expansion of forest-based rural

development sectors; and prevention

of illegal occupation of forest lands

and other forest offences through

people's participation. The policy

statements envisage: massive afforestation

on marginal public lands through partnerships

with local people and NGOs; afforestation

of denuded/encroached reserved forests

with an agroforestry model through

participation of people and NGOs;

giving ownership of a certain amount

of land to the tribal people through

forest settlement processes; strengthening

of the Forest Department and creation

of a new Department of Social Forestry;

strengthening of educational, training

and research facilities; and amendment

of laws, rules and regulations relating

to the forestry sector and if necessary,

promulgation of new laws and rules.

Thus, over time the policy has shifted

somewhat from total state control

to a management regime involving local

communities in specific categories

of forests.

Acts Forest legislation

in Bangladesh dates back to 1865,

when the first Indian Forest Act was

enacted. It provided for protection

of tree, prevention of fires, prohibition

of cultivation, and grazing in forest

areas. Until a comprehensive Indian

Forest Act was formulated in 1927,

several acts and amendments covering

forest administration in British India

were enacted and were as follows:

(a) Indian Forest Act, 1873; (b) Forest

Act, 1890; (c) Amending Act, 1891;

(d) Indian Forest (Amendment) Act,

1901; (e) Indian Forest (Amendment)

Act, 1911; (f) Repealing and Amending

Act, 1914; (g) Indian Forest Amendment

Act, 1918; and (h) Devolution Act,

1920.

The Forest Act of

1927, as amended with its related

rules and regulations, is still the

basic law governing forests in Bangladesh.

The emphasis of the Act is on the

protection of reserved forest. Some

important features of the Act are:

(i) Under the purview of the Forest

Act, all rights or claims over forestlands

have been settled at the time of the

reservation. The Act prohibits the

grant of any new rights of any kind

to individuals or communities; (ii)

Any activity within the forest reserves

is prohibited, unless permitted by

the Forest Department; (iii) Most

of the violations may result in court

cases where the minimum fine is Taka

2,000 and/or two month's rigorous

imprisonment; and (iv) The Act empowers

the Forest Department to regulate

the use of water-courses within Reserve

Forests.

An amendment of the

Forest Act of 1927 was drafted in

1987 and approved in 1989, as the

Forest (Amendment) Ordinance 1989.

The Forest Act was further amended

in 2000 and renamed as the Forest

(Amendment) Act, 2000. Under this

amendment some major changes have

been brought in the Act.

For assuming control

of private forests and wastelands

by the government in the interest

of conservation, the Bengal Private

Forest Act, 1945 was passed; but partition

of India in 1947 intervened and the

Act could not be put into effect.

After partition, in 1949, East Pakistan

reenacted the provisions of the Bengal

Private Forest Act. This was passed

in 1959 as The East Pakistan Private

Forest Ordinance. The private forest

and wastelands taken over by the government

were to be managed as a distinct legal

category, ie, vested forests. The

ordinance had 64 clauses and detailed

provisions for the management and

protection of vested forests. Vested

forests were taken over by the government

from their private owners for a period

of one hundred years for the purpose

of conservation and afforestation,

since they were not being cultivated

properly by their owners.

Degradation:

forest resources Degradation of forests

and their resources have been occurring

due to manifold reasons. Among others,

principal causes of forest destruction

include uncontrolled deforestation,

new settlements, illegal wood cutting

and felling, leaf-litter collection,

dependency on forests for fuel wood,

grazing and browsing, intentional

forest burning, 'Jhum' or shifting

cultivation, conversion of forest

lands into agricultural land, overexploitation

of particular economically important

species such as medicinal, fodder,

dye, etc, indiscriminate use of forest

wood in brick fields and in other

small industries, and total clearing

of undergrowth and excess consumption

of forest materials for domestic purposes.

In addition, heavy rainfall, occasional

landslide, erosion, flood, cyclone

and tornado, increase of salinity,

and some diseases (eg top dying disease

in the Sundarbans) are also major

causes for forest lands and forest

resources degradation.

Moreover, lack of

proper management and awareness, inadequate

research and developmental programme

on habitat and resource and regeneration,

restoration and conservation are also

some additional reasons for the degradation

of forest resources in Bangladesh.

Sometimes the rate

and pattern of forest degradation

vary with the type of forests and

their geographical location. For example,

sal forests of Bangladesh are located

in the middle and northern part of

the country, which are topographically

almost plain lands, and dry in nature.

Owing to geographical position and

edaphic conditions, the scope and

the rate of degradation in sal forests

are higher due to easy encroachment

and illegal settlements.

Pests and diseases

of forest trees Pests- Larva of the

moth, Agrotis ipsilon, known as cutworm,

commonly feeds on seedlings of a number

of forest plants. They hide in burrows

3-8 cm deep in the soil during the

day and come out to the surface at

night. The stems of young seedlings

are cut down at ground level but occasionally

buds or new leaves are also cut. Cockchafer

or white grubs of the beetles Leucopholis,

Holotrichia, and Anomala sometimes

cause serious damage to seedlings

of teak, rubber, babul, jarul, minjiri,

etc. The larva feeds on small roots

and sometimes cut tap root at 5-10

cm below the soil surface. The infested

seedling wilts and ultimately dries

up.

The adult feeds on

the foliage of many trees.

Some termites, including

species of Odontotermes and Microcerotermes

attack young seedlings, saplings,

implants or cuttings in nurseries

and plantations of many forest trees.

Termite attack occurs below the ground

level in the upper 20 cm of the soil

layer. Usually the bark of the tap

root is completely eaten up. The affected

seedlings/young plants show signs

of wilting, resulting in death.

Teak is attacked

by two major lepidopteran defoliators.

These are Hyblaea puera and Eutectona

machaeralis. The mature larvae of

the former consume the entire leaf,

leaving only the mid-ribs and major

veins. On the other hand, the larvae

of E. machaeralis consume only the

green layer of leaf leaving all the

veins intact, thereby skeletonising

the leaf which later turns brown and

dries up.

The young larvae

of gamar defoliator, Calopepla leayana

(Chrysomelidae: Coleoptera) feed mainly

on the undersurface of gamar (Gmelina

arborea) leaves, leaving only the

mid-ribs and main veins intact. The

adult beetle feeds on the leaf, cutting

large circular holes, and also eats

young buds and shoots. Mahogany shoot

borer, Hypsipyla robusta (Pyralidae:

Lepidoptera) is an important pest

of mahogany, toon (Toona ciliala)

and chickrassy (Chukussia tabularis).

The larva bores into the shoots of

the young trees.

Widespread mortality

of Babla (Acacia species) is caused

by the scale insect, Anomalococcus

indicus (Homoptera). The insect sucks

sap from the tender shoots and branches.

In case of heavy infestation, the

shoot is completely encrusted with

the scale insect. The attack is more

severe during November-April.

The larva of Ommatolapus

haemorrhoidalis (Curculionidae: Coleoptera),

commonly known as cane top shoot borer,

bores into the growing shoot of cane.

The larva makes a central tunnel inside

the shoot to feed on the soft internal

tissue.

Koroi (A1bizia species)

is frequently attacked by two major

defoliators, Eurema blanda and E.

hecabe. The young caterpillars nibble

leaflets and as they grow older, they

start eating entire leaflets, leaving

behind only the mid-ribs. In severe

attacks the plants are completely

defoliated. Young plants are mostly

preferred, but older trees are not

spared.

Diseases Dieback

of keora is a serious disease of keora

seedlings. The first symptom appears

as a rot from the tip, middle, or

lower tender portion of the stem.

Affected seedlings decay out from

the top. The disease is caused by

the fungus, Chaetomella raphigera.

Bamboo blight disease

often causes severe mortality of young

bamboo culm. It has been observed

in the country for the last two decades,

and is most prevalent in greater Rajshahi,

Chittagong, Comilla and Sylhet districts

in decreasing order of occurrence.

Bambusa balcooa and B. vulgaris are

the most affected bamboo species of

Bangladesh. The causal fungus has

been identified as Sarocladium oryzae.

Over the last few

decades, a root rot causing dieback

of Lohakat (Xylia oxlocarpa) has been

observed in some plantations in and

around Lawachara of Maulvi Bazar district.

The first symptom is the appearance

of pale green colour of the foliage

of one or more major branches. Later,

the foliage becomes yellow, and eventually

falls off.

Recently a disease,

called pink disease, caused by Corticium

salmonicolor, has been recorded on

Eucalyptus in some plantations of

Chittagong, Cox's Bazar, and Sylhet

Forest Divisions. The most striking

feature of the disease is the mortality

of the major branches accompanied

by leaf cast due to invasion of the

pathogen, which in severe cases may

spread to the crown. The first symptom

appears as an exudation of gum on

the stem or branches, followed by

a growth of white silky threads on

the surface of bark. [M Wahed Baksha]

Forest Department

a Department of the Ministry of Environment

and Forest, and is headquartered at

Mohakhali, Dhaka. A Chief Conservator

of Forests, assisted by three Deputy

Chief Conservators, heads the agency.

It is responsible for forest development

and management planning and forest

extension. The Department has a number

of institutes under its administration

and supervision and these include

a Forest Research Institute and a

Forest College at Chittagong, a Forest

Development and Training Institute

at Kaptai, and two Forest Schools,

one at Sylhet and the other at Rajshahi.

The National Botanical Garden located

at Mirpur, Dhaka is also under the

administration of the Department and

this Garden as well as the Rajshahi

Forest School has tissue culture laboratories.

Besides, the Department implements

a good number of projects and some

of such projects being implemented

from 1990s are the Forest Resource

Development Project, Forestry Sector

Project, Coastal Green Belt Project

and Conservation of Biodiversity in

the Sundarbans Project.

The field operations

of the Department are managed through

six Circles and each Circle has several

forest divisions, the total number

of which is 37 in the whole country.

The divisions are divided into several

forest ranges controlled by Forest

Range Officers, under whom there are

Beats under the charge of Beat Officers

of the rank of Forester/ Deputy Rangers.

The Forest Department has introduced

social forestry activities by involving

people to rehabilitate degraded forestland

as well as marginal land. These activities

include woodlot/block plantation,

agroforestry plantation, strip plantation,

rehabilitation of jhumias (tribal

people living on shifting cultivation),

village afforestation, seedling distribution,

nursery development and training.

The Department has

adopted a Resource Information Management

System (RIMS) that helps significantly

in forest development planning and

monitoring of all regular and project

activities. Integrated with the Geographical

Information Systems, the RIMS has

become an important arm of the Forest

Department as a coordinated centre

for data and information on forest

resources and their management in

Bangladesh. The total number of employees

working in the Forest Department is

about 7300 and besides, the Department

employs a large number of labourers

on a casual basis for its field activities.

Forest education

and research Formal education and

training for personnel working in

forest services were not available

in this subcontinent until 1870s.

From 1878, the Government of British

India started training programme of

the recruited foresters to provide

skilled technical manpower in respective

forest territory.

A forest policy was

adopted in 1894, after about 30 years

of establishing the Forest Department

in undivided India. The subject forestry

as science thus started developing

slowly and gradually in the sub-continent

for the purpose of exploitation of

the vast forest resources by the British

Government. With such a background

and interest the British Government

felt the need of promoting Forest

Education and initiating research

facilities in this part of the country.

During 1926 to 1932, the gazetted

officers of the Indian Forest Service

received training at Dehra Dun. In

1937 with the provincialisation of

the forest services, gazetted officers

started getting training since 1938

for provincial forest services.

After creation of

Pakistan, a forest college was established

in Peshawar, West Pakistan to train

gazetted and non-gezatted forest officers

recruited by the Public Service Commission.

A Forest College was established at

Solasahar in Chittagong for providing

two years diploma course in forestry

for the non-gazetted range officer

recruits of the government, autonomous

and private sector enterpreneurs.

The Institute of

Forestry was established at the Chittagong

University campus in 1976. The institute

offers four-year undergraduate courses

and one-year masters course.

In 1955, a forest

research laboratory named as 'Forest

Product Laboratories' was established

in Chittagong aiming for better utilization

and innovations in this sector. Subsequently

in 1968 it was converted into a full-fledged

Forest Research Institute. The mandate

of the Bangladesh Forest Research

Institute (BFRI) is to conduct research

on the problems faced by and programmes

undertaken by the Department of Forests,

bangladesh forest industries development

corporation (BFIDC) and other concerned

government and non-government organisations.

Source: Banglapedia,

National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh

Asiatic Society of Bangladesh